The West is in decline. After more than a decade of populist insurrections followed by a global pandemic, and the return of war to eastern Europe, the idea is widespread, even accepted.

These narratives suffuse the political right, which often yearns for lost values. Remember the 1950s: the consensus society, privatism, and traditional gender roles – an arcadian vision of things before they fell apart. Further to the right, civilisational undoing usually comes spiced with racial paranoias, laments for the loss of national vigour, and nods in the direction of Oswald Spengler.

But the left, at least in its welfarist guise, has its own nostalgias. It looks back at the age before Thatcher and Reagan. Then, the state provided greater entitlements, trade unions were stronger and democracy more robust. Thatcher and Reagan promised more personal freedom and economic growth, but delivered inequality instead. Another story of decline. Even radical-liberal culture warriors look backwards. In their railing against racial, sexual and gender oppression, they act as if the last half century hadn’t happened.

Both left and right ache for a return to the postwar era’s certainties. All could credibly mount a case that things were better then. The picture they all paint is the same, they just choose to focus on a different stretch of the canvas. These decline narratives testify to the loss of a social order underpinned by strong, continual economic growth and human development.

And in the West the order came to an end in 1973. It has just taken 50 years for consciousness of this decline to become widespread.

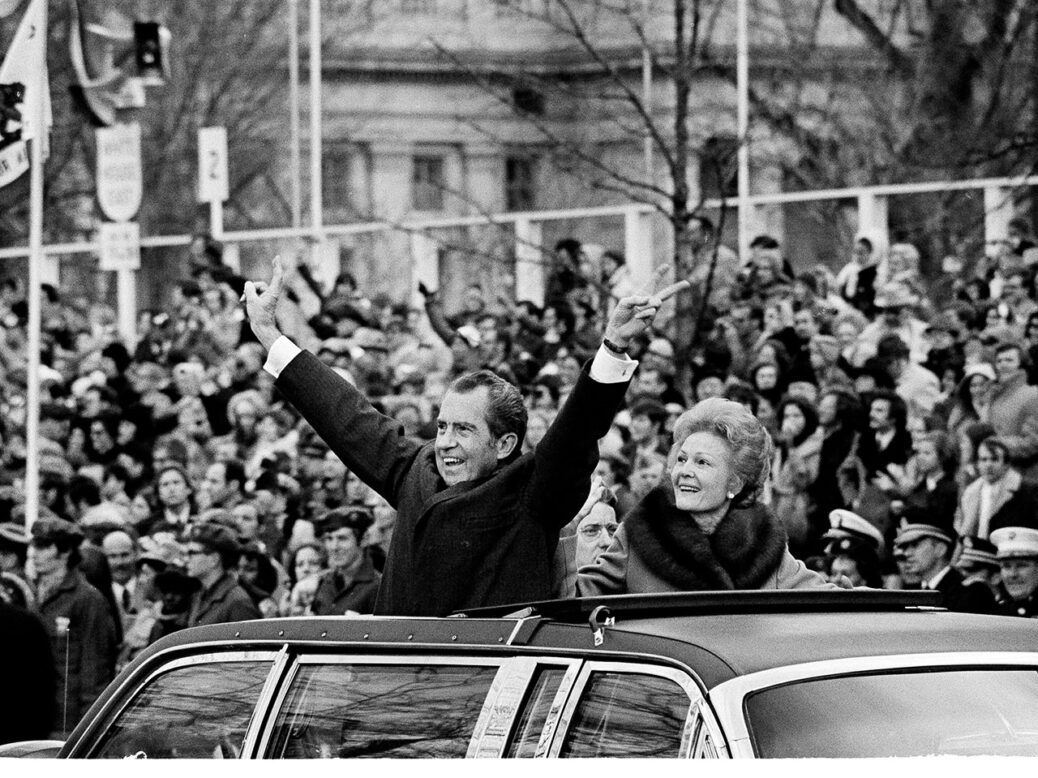

1973 was the year the West never recovered from. The oil shock induced by Opec marked an end to cheap energy, with ensuing inflation and economic slowdown generating a crisis that would lead policymakers to reach for new, liberal solutions. Pinochet’s coup in Chile that year was the first, brutal salvo in that counteroffensive. In the United States Richard Nixon’s inauguration for his second term as president indicated that the wave of radical energy that peaked in 1968 had ended. Radicals instead channelled their energy into cultural matters, finding politics and the economy intractable. This was to transpose political contestation onto a terrain where questions of self and being, of identity, took precedence over those of security, wealth and its distribution. Cultural progressivism and its conservative backlash would be the template for five decades. The exponential increase in American mass incarceration began that year too, testifying to a society that no longer believed it could solve social problems through a more inclusive society.

Technological advancements would increasingly become about communication and health rather than transportation or construction. Here were the seeds of the digital age, and confirmation that the West was turning inwards, and becoming ever more atomised. The first mobile phone call was made in 1973. If you wanted a single image that encapsulated these patterns of decline, then consider the famous alligator chart showing the divergence of wages from productivity in the United States: while the former stagnated, the latter continued growing. The hinge of the alligator’s jaw? The year 1973.

The balance sheet of the past 50 years has been stark. Western political institutions are no longer responsive to the popular will even if the institutions formally look the same. Western societies are depressed and atomised, easy prey for demagogues. Western culture has been rendered flat and lifeless by commodification. Western economies are stagnant: though productivity has vastly outstripped wages, productivity growth has declined, leaving society ever more unequal at a time when material progress means little more than the latest version of an old Apple product.

Many might be tempted to throw all of this in the big bucket named “neoliberalism” and be done with the conversation. That suggests the travails of the last five decades were simply the story of a wrong policy turn. If that were reversed, the West could be restored to its glory days.

A return to the postwar settlement is now impossible. It was a historically unique arrangement. High growth emerged because of the destruction of capital in the Second World War, with the world economy growing 5 per cent a year from 1951 to 1973. That figure now hovers around 3 per cent at best. On a per capita basis, it is down to 1.5 per cent a year. The Western postwar political consensus, when the working classes were given confidence by low unemployment and the spread of consumer durables, and elites were disciplined by the experience of war and the threat of revolution, no longer exists. To bring those arrangements back would require another war of the same scale. Viewing that period as a baseline of what the West “should be like” is a grave mistake. Those that do so, on both the left and the right, are confusing a historical exception for an ideal. To insist on a return to these conditions is mere nostalgia.

When I propose that the West ended in 1973, I don’t mean that it was the best of all possible worlds. No one politically active then would be that upbeat in their estimation. Western democracies were marked by racial and sexual oppression; while workers’ wages increased, so much of life then seemed stultifying. Both the 1960s New Left student-powered revolts against alienation and the Thatcher-Reagan counterrevolution in the name of individual liberty testified to this sense of being stuck. Indeed, the crisis of the 1970s was also a crisis of excess demand. “Stagflation” reflected this contradiction: the combination of demands placed on the state with an economy that could no longer supply the goods.

[See also: Anarchy unbound: the new scramble for Africa]

It’s true that Western decline is mostly relative, rather than absolute. The West’s loss has been others’ gain. When poverty statistics or similar indicators are taken into account, the overall global picture doesn’t look too bad, as the Steven Pinkers of the world love to insist. But subtract China from your accounting and suddenly those lines shooting up look rather flat.

The dark reality is that we are faced with a global slowdown and a reconfiguration of the economy in which there is little prospect of most of the world catching up. The West has reached the end of its developmental road – but so have so many other countries. Poor countries have scant opportunity to industrialise; many will never become middle-income countries. Middle-income nations, meanwhile, find themselves in a trap: rising costs and declining competitiveness. They are deindustrialising, which the West as a whole began doing decades ago.

And here, again, we can look back to 1973 as a turning point.

In the early 1970s the Bretton Woods international financial system came to an end. The relatively stable global economic order began to unravel. Capital controls were relaxed, while the rise in oil prices in 1973 led to an influx of petrodollars into new financial markets. The explosive growth of international capital markets was, in fact, the entry of a new factor into international affairs, one that would become almost a distributed but global sovereign: the giant vampire squid of global finance. Composed of various funds, banks and markets, and supported by key adjuncts like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it would evolve into the final arbiter on national, developmental trajectories.

For a while, these new capital markets allowed sovereign states to borrow on the prospect of continuing strong growth. But then the US jacked up interest rates in a 1979 event known as the Volcker Shock. Servicing that debt became unbearable, leading to a “lost decade” across Latin America and beyond. Brazil is a good example of the new disposition. From 1960 to 1980, its real per capita GDP increased by more than 140 per cent. From 1980 to 2000 it grew by less than 20 per cent. Sovereign debt crises became a recurring phenomenon. The tentacles of global finance strangled a series of countries in turn: Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Thailand, Indonesia, Russia, Argentina (again), Greece and more.

This period marked another turning point too. It was not just the burden of debt and the globalisation of finance that put paid to the dream of global equality. Industry of the kind that depended on things like rubber, petrol and steel (automobile manufacture, for instance) ceased to be the leading edge of value-added goods. The really high-value stuff is increasingly immaterial, protected through intellectual property rights. Barred from entering the game, but outcompeted by China, many middle-income countries are undergoing a frightening tendency: “premature deinudstrialisation”.

Recall all the complaints you’ve heard in Britain or the US – initially on the left but now increasingly on the populist right – about the long-term negative effects of deindustrialisation. Now imagine going through the same process but at a much lower level of income. This is the reality for those middle-income countries lucky enough to have industrialised at some point in time, but unlucky enough to know that process only in past tense.

Now imagine industry isn’t growing and providing jobs, but old-fashioned agriculture has disappeared too, leading masses to abandon the countryside and move into the city. With only precarious work in services on offer, deagrarianisation and deindustrialisation results in what the geographer Mike Davis called a planet of slums.

This isn’t to say that the median worker in South Africa or Brazil, Senegal or Myanmar – or Spain or Belgium for that matter – was better off materially in 1973. After all, back then many new states were struggling to find their feet while liberation movements faced imperial aggression and death squads. Living standards have improved over the past 40-50 years. But, crucially, often by much less than expected, and in some cases hardly at all.

Indeed, we shouldn’t seek to measure things in a flatly empirical way. The world is not a graph produced by the World Bank. What is also contains what might be. How much possibility an age contained is as important as the actuality of what it delivered. We must look not just to the accumulation of material – and, indeed, moral – progress but also to how germinative an age is, what paths it holds open for different futures.

In this sense, 1973 can serve as a sort of peak from which we have declined, either in actuality or prospectus – or both. For advanced Western countries, extraordinary growth pointed a way forward, while for the less developed, capitalist development and catch-up seemed a genuine possibility. For those on the left, socialism was the next stage to be reached, whether it was to emulate existing regimes or be something new entirely.

Today it seems that limited ambitions are complicit with the situation. Limited expectations reduce pressures on political leaders. We may believe they do not or cannot have the solutions, but that is ever more reason to apply pressure, to begin pointing beyond a global order that disserves most of our species.

The economist Marc Levinson once observed that the Golden Age ended in 1973, but noted that we have been left with “unrealistic expectations about what governments can do to assure full employment, steady economic growth and rising living standards”.

The reality is that we demand too little. Debt-burdened poor countries do the bidding of the IMF and creditors. Crisis-ridden southern Europeans remain wedded to the structures of European “unity” when they clearly hinder any prospect of growth. Americans accept there is nothing beyond the two-party system and the global trade system.

When poor countries strive to break free of a global system that mainly serves the rich minority, they are crushed. Hence so few try. Rich countries, on the other hand, have up till now not been willing to countenance the disruption that a radical break would entail – even when the political will has been summoned. This is what we saw with Brexit: constitutional change has not provoked an economic reckoning as elites sought to keep things much the same as they were before. A new developmental project in Britain was stillborn.

Levinson notes that today “voters are again turning to the right, hoping that populist leaders will know how to make slow-growing economies great again”, but doesn’t believe they will do much better. Probably not, but it is not the demand that they should that is the problem. Nor is the dream of a world of greater national autonomy and popular sovereignty. What is at issue is that the scale of ambition – both theirs and ours – falls short.

There is no going back to 1973. But if we can reflect on our decline, on the reality that these are all “lost decades”, this might serve to provoke new thinking. 1973 should serve as a reminder not of an ideal world to be recaptured but of a world of greater possibility.

[See also: We are still living with the wreckage of liberal globalisation]